I used to play a lot of Go around 2010-2016. I am not a very strong player however. My European rating is 2 kyu, which corresponds to a somewhat average club player in Finland.

I remember that studying Go used to be difficult because there were no good computer programs to learn from. If you wanted to know how to improve your game, you had to ask a stronger player for advice. However these stronger players were not always available, and sometimes they gave conflicting advice.

Then, in 2016, AlphaGo happened. This was an AI that for the first time reached and surpassed human professional playing strength. Unfortunately, the program was not publicly available, and even if it were, it required an expensive cluster of 48 tensor processing units to run, making it unavailable for the average Go player. Around this time my interest in Go faded.

Now, in 2022, there are open source projects that replicate and improve upon the architecture in AlphaGo. The neural network has been made more efficient so that it is possible to have a professional-strength AI running on a home PC. There are also graphical user interfaces that help exploring the game tree variations calculated by the AI. Could these new tools help me improve my game?

Lessons

I have been playing Go again at the KGS go server for the past month. Most of my games are on my account that is firmly stuck in the rating of 1 kyu (KGS 1 kyu is roughly equivalent to European 2 kyu). I also have another account which is at 1 dan, which I use only when I feel that I’m focused and playing well.

After each game, I have loaded up the game in Katrain, which is a graphical user interface for the Katago AI. The AI runs on my Nvidia RTX 2070 GPU. In this post I write about the things I have learned from studying with the AI. If you’re not a Go player, the rest of the post will be hard to follow. To learn Go, try this guide, which I myself originally used to learn the rules.

Lesson 1: The opening does not matter

When studying Go with stronger players at the club, we would often have long discussions about opening strategy. Things like which corner approach to use, which joseki to choose and which side extension is the best. After looking at many openings with the AI sensei, I’ve come to the conclusion that the opening does not really matter. All moves that follow standard opening principles are usually OK. Some move may be 1 point better than the other, but in the grand scheme of things, at the 2 kyu level, that does not really matter much.

Using video game terminology, the purpose of the opening is actually to set up the map of the game. In games like Starcraft there are only a few maps available for ranked play. In Go, you and your opponent build a new map for every new game. If you want an influence-oriented map, you can play a lot of stones on the fourth line. If you want a territory-oriented map, you can try the 3-3 point. It’s a blessing that all of these choices are more-or-less valid ways to play, at least in average amateur play.

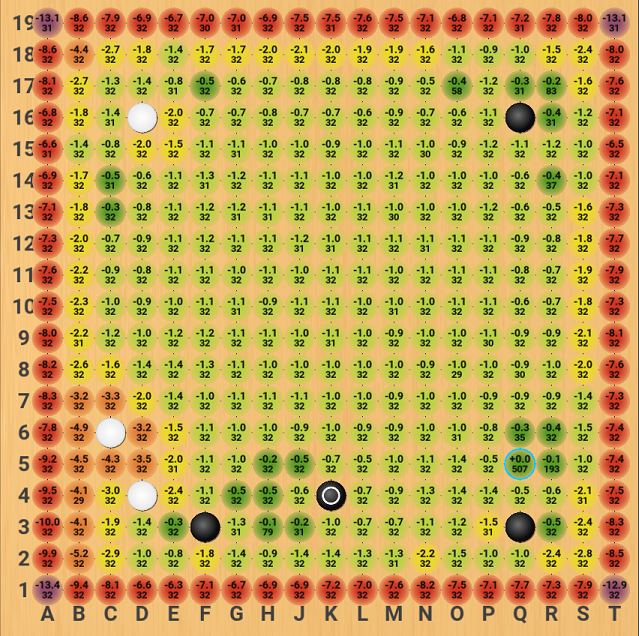

Move 8 of an opening: white to play. The numbers on the moves are the expected point loss compared to optimal play. Almost all moves that are on the third line or above are playable. All normal corner approaches are good.

There are a lot of non-josekis that are only slightly worse than the best sequence. You don’t have to know the most accurate variants. Often you can play something almost as good and lose only 1-2 points. This loss is negligible compared to losses in the middlegame.

Lesson 2: The endgame does not matter

In a game with two equally matched opponents, the score rarely moves more than 8 points total during the endgame. It’s not because both players are playing perfectly, but because both players play at roughly similar accuracy and the mistakes cancel out. On the other hand, during the middlegame, the score usually swings wildly from -30 to +30 points or even more. A single bad move in the middlegame can undo everything that you can realistically gain with careful endgame. Thus, studying and optimizing the endgame is not very important on my level.

Lesson 3: The actual game happens during the middlegame

The middlegame is where games are won or lost. It feels like every other move presents a tough choice. For example, is it possible to hane here? Which one of my groups needs the most help? Is it possible to tenuki yet? Is this peep sente? Is it possible to invade? Does this cut work? Et cetera.

A very significant number of games are decided by one of the players misreading a life-and-death problem. Even if no group dies, playing an extra move to a group that does not need it can cost more than 10 points because it sometimes is not much better than passing. Even if it does not straight up win you the game, life and death often influences things like whether a move is sente against a group, which is very important to know.

A lot of games are decided in a big capturing race. Learning a good intuition for whether a capturing race is favorable is very important. Once the race has started, it will win you games if you know the right techniques and tesujis to minimize the opponent’s liberties and maximize our own.

Judged by the AI, an average KGS 1 dan player is actually pretty bad at life and death and capturing races. It seems to me like if you are just good at these things, you could easily be 3 dan or better even if you don’t know much about opening theory or endgame.

Lesson 4: Shape is important

A lot of Go playing strength is just having a mental database of strengths and weaknesses of particular shapes. You should have a strong prior toward playing good shapes, and deviate only when you have a very specific explainable reason against it, like having to cover a cutting point.

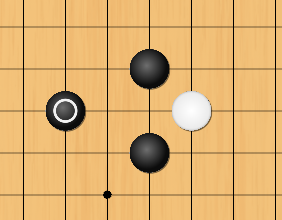

Many times during a game I knowingly played a bad shape because I thought that situation was an exception. It usually wasn’t. As a lesson I would probably do better if I just never played some bad shapes, like this one:

Playing one line above or below the circled move is almost always better.

Final thoughts

I feel like AI has helped me a lot to focus my efforts on things that actually matter in my games. I try to ignore small mistakes that are less than 1.5 points and instead focus on larger mistakes and try to figure out why they are mistakes. Usually it is quite obvious in retrospect.

It seems to me that most of my losses currently are due to bad tactical judgement and misreads. I still mess up life-and-death problems that a 10 kyu could solve. But on the bright side, my opponents at KGS 1 dan are making similarly bad mistakes. It seems at least feasible to reach KGS 2 dan or stronger with practice. There are no mysterious dark arts to learn to play at that level – just play solid and don’t screw up so much. Easier said than done, huh?